[dropcap]D[/dropcap]espite the current situation the world finds itself in, some things remain the same. French giants Olympique Lyon have been confirmed as the French champions for an incredible 14 consecutive seasons, but whether they get the opportunity to win a fifth consecutive UEFA Champions League remains to be seen.

With the backing of president Jean-Michel Aulas — and despite regular changes in managers — Lyon has continued to be the dominant force in European football. But it wasn’t always this way, and 10 years ago they didn’t have a single European title to their name, let alone the six they now hold a decade on.

Breaking Through

It was on May 20, 2010, in Getafe’s home stadium in Spain that Lyon took the first small steps toward the dominance and status they enjoy today. In the first final since the competition moved under the official UEFA Champions League banner (the first one-legged final), Lyon went up against German giants 1. FFC Turbine Potsdam, winners of the 2005 tournament.

It was Germany who dominated the landscape, both domestically and on the international stage. The German National Team had won five European Championships in a row heading into 2010, while club sides had won four of the previous five European Cup finals, with 1. FFC Frankfurt and FCR 2001 Duisburg joining Potsdam in winning the trophy.

French teams had not yet proven a threat at the European level. Juvisy didn’t make it out of the group stage in 2007 before Lyon took over as the dominant French side with their first league title the same year.

In 2007, Lyon’s first year taking part in the European Cup, the club knocked out previous winners Arsenal before losing to Umeå IK in the semifinals; another semifinal defeat to eventual winners Duisburg followed 12 months later.

Lyon was third time lucky in 2010, defeating Umeå to reach their first final, a final that would prove to be a real nail-biter and one in which the French side inadvertently threw away a potential first title in a dramatic penalty shootout.

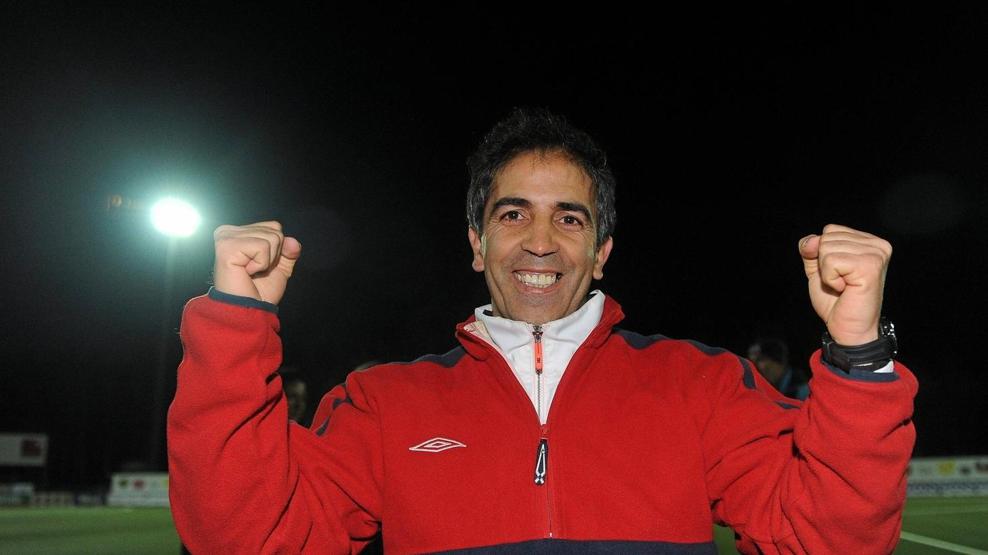

But their journey to get there had been a long one, as manager at the time Farid Benstiti could attest to after joining the club almost a decade earlier in 2001.

After a few seasons treading water, everything changed when president Aulas took the women’s team into the club and set about turning them into the dominant force they are today.

“The president let me work on the long-term future of the team,” said Benstiti, who also previously played for Lyon in the 1980s. “He never asked for quick results, we were not in a hurry to have immediate results. I had friends, older and wiser than me in the club, they helped me a lot.”

Between them, Benstiti and Aulas set out four principles to follow when it came to turning Lyon into not just a dominant force in France, but in Europe too.

The majority of it surrounded recruitment, combining not just the best foreign talents, but both experienced and up-and-coming talents from within France, the latter of whom would became mainstays of the Lyon team even up to the present day.

Lyon set about taking the best players from their rivals as they entered the back half of the 2000s. Louisa Nécib, Sonia Bompastor, Hoda Lattaf, and Elodie Thomis all arrived from Montpellier while goalkeeper Sarah Bouhaddi would arrive from Juvisy.

Players who remain at the club to this day, such as Wendie Renard and Amandine Henry, arrived as teenagers via INF Clairefontaine, France’s national football center, while Laura Georges was signed after a three-year spell playing college soccer in the United States. Swedish icon Lotta Schelin was signed from abroad but missed the 2010 final through injury.

“We looked at the top foreign players,” recalled the manager at the time. “I brought Lotta in who was very young at the time. Players like Shirley Cruz and Lara Dickenmann. We recruited the best French players over a number of years. Nécib, Renard, Eugénie Le Sommer, Henry, Camille Abily, Thomis, and Bouhaddi.

“Our second principle was to give them the best conditions in Europe. We worked with the federation to create professional contracts so the players could be 100 percent professional. We decided then to help them with their studies, working with them for a plan after their career.”

The third and fourth parts of the plan also largely came off the field, ensuring the players had the best environment possible to succeed.

“Slowly but surely we offered them a very good structure,” added Benstiti. “We improved the pitches, the locker rooms, the medical side, how we traveled, we made sure they came to football with the best conditions. On the financial side, we had the same as the men. The same marketing, the same sponsors, that was very important for developing our women’s team.

“The final part was to build a very good academy like the boys had. There was big potential and some very good young players in the Lyon region.”

One of the players Benstiti mentioned was Switzerland’s Lara Dickenmann. A versatile forward, like Georges, Dickenmann joined out of Ohio State in the U.S. college system after Lyon had already established themselves as the top side in France.

Dickenmann joined Lyon halfway through the 2009 season. The next season saw Lyon reach their first Champions League final.

Fifteen goals in 21 league games had established Dickenmann as a regular starter and a key player and while she could see the path the club was on, there was still a lot that needed changing over the course of those next few years.

“I got to visit the construction site for the new ground and facilities,” said Dickenmann, now of Germany’s VfL Wolfsburg. “In 2010, we were training at the old stadium. The men had their private club-owned site on the right side of the street and we were on the other side.

“The locker rooms weren’t great. We would meet up there but most people usually got changed before coming in. I left my shoes in there once and they were gone the next day, but it changed so much.”

She added, “Eventually we moved to the other side and we were on the private club-owned side. The pitches were amazing, you can’t say anything bad about them, but the locker rooms in the early days weren’t great. I think now the Lyon players have everything the men do.”

It was president Aulas who was the man behind every positive change happening off the field in his determination to make his club the best in the women’s game, and both Dickenmann and Benstiti can only praise the influence he had over the years they spent at the club. Benstiti left after the 2010 final but Dickenmann remained until she joined Wolfsburg in 2015.

“He was very involved,” said Dickenmann. “He took the decision before I joined to integrate the club and he was always very present. Before games he had come into the locker room and tell us what it meant to the club to win, what our mentality should be. The coach always picked the game and prepared the game but the president would always give us a meaningful message about what we meant to the club.

“He wouldn’t just come to the big games, he’d come to smaller games in front of 300 fans. Even back then, I talk about the locker rooms but we still had more than most other teams, we were able to be professional even at that time, we could just think about soccer and he was the one who made that possible.”

Benstiti added, “He was the key to the system. He was able to understand quickly what the women in our club could do and how they could be so important. Very soon he decided he wanted to be the best in Europe, because it was easier with the women than the men.

“The women became another way to talk about Lyon, but I’m sure he didn’t do it just for interest. He really liked women’s football and his players and he is still passionate even today about his team.”

The First Final

Benstiti and Dickenmann were embarking on different stages of their careers by the time they reached their first Champions League final.

The manager would leave after the final and go on to coach the Russia national team a year later, while Dickenmann’s time at the top was just beginning.

Turbine Potsdam, with their completely German starting eleven stood in Lyon’s way, with substitute Yuki Nagasato the only player on the roster from outside the country.

Potsdam had Anna Sarholz in goal who would play a huge role in the final, as well as big-name players such as Babett Peter, Josephine Henning, Nadine Kessler, and Anja Mittag.

Lyon’s team by this stage was more multi-national. Seven French players lined up alongside Dickenmann, including Sweden’s Amelie Rybeck, Costa Rica’s Shirley Cruz, Norway’s Ingvild Stensland, with Brazilians Simone and Kátia on the bench.

It was a tight and tense finale, a 0–0 draw after a hard-fought 120 minutes meant a penalty shootout to decide the tournament’s first one-legged final.

After Potsdam captain Jennifer Zeitz and Mittag were denied by Bouhaddi, Lyon had to score just one of their last two penalties to take their first title, but almost unbelievably Sarholz denied Amandine Henry and then Isabell Herlovsen.

Lyon ironically scored their next three penalties in sudden death, but Elodie Thomis struck the crossbar and the title cruelly went back to Germany.

It was a tough end for Benstiti who admits everybody at the club that day felt excitement at the prospect of a first European title, but Dickenmann had a different attitude, one she admits she wouldn’t have as a more experienced player 10 years on.

“It was the beginning of my professional career so maybe my standards at that time were different to some of the other players,” she laughed. “In that game, we lost by so little, we could have won and afterwards I just felt proud to have been there.

“It was my first final and you never know if you’ll be in another one. It was hard to be heartbroken; if it was now, I’d be devastated. Every German team at that point was huge and we respected them a lot. I spoke to a few of their players and for them it was the other way around, but we felt like the underdog.”

She added, “I remember thinking like, if we won, I could quit. I’d have won everything, what would I do next?! I was completely overwhelmed that whole day. Afterwards I did an interview on German TV and they told me they’d never seen someone so happy who had just lost. I hope I wasn’t smiling too much, I think I was just overwhelmed, but I definitely wouldn’t react like that today.”

Dickenmann describes Potsdam as “machines” and believes other teams couldn’t at that time match up physically to the German sides who had been at the top for so long, but Lyon wouldn’t have to wait too long to take that next step, but it would be without Benstiti.

“I don’t know if I would have stayed if we won the final,” said the former manager. “It was a good time to go because I worked there for a long time. After those experiences I could already say that my career had been a good one.

“I worked to put Lyon at the very highest level and for a long time I was sure about the success. There was no doubts because the players I brought in had exceptional talent to last at the highest level for a long time with Lyon.”

Aftermath

Twelve months later at Fulham’s Craven Cottage, now under the guidance of Patrice Lair, the same two sides would meet in the final again, this time Lyon came out on top in a 2–0 win, with Dickenmann scoring the clincher with five minutes to go.

Another title arrived a year later in front of 50,000 partisan German fans in Munich against Frankfurt, before defeat to Wolfsburg in 2013.

With two consecutive titles under their belt, Wolfsburg signed Dickenmann in 2015 but since then it has been the French side who has dominated the European landscape, with another four titles in a row since 2016.

But everything had changed by the time Dickenmann left, and she believes her current side has never been too far off her former team despite two painful defeats in 2016 and 2018.

“The biggest change was the new stadium and the new facilities,” she recalled. “In terms of recruiting, that was huge. Not many teams had those kinds of facilities and I’m sure that was a big help in getting the top players to keep joining.

“They get to play some of their games in the main stadium and they just recruited a lot of great players. The players grew together, they bought players in their peak, everything came together for them.”

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]ickenmann lined up for Wolfsburg against Lyon in the 2016 final, with the end result eerily similar to the final back in 2010. Like Lyon six years earlier, Wolfsburg missed their final two penalties after Ada Hegerberg had missed Lyon’s opener, but it was the French side who took home the trophy.

The sides met again two years later in Kiev and after a taut and scoreless 90 minutes, Pernille Harder put the German side ahead early in extra time. But a red card for Wolfsburg’s Alex Popp and the introduction of Shanice van de Sanden for Lyon saw them fire home four goals in quick succession to down Dickenmann’s side yet again.

“The penalties in 2016, they dominated the game but we made it to penalties. It was still tight. We lost some games in quarterfinals which were not tight at all and even the one two years ago, we took the lead.

“I don’t know, we would try to put up a good fight and I think we were the only team who could do that. We got a red card and we struggled physically. We played 120 minutes and penalties against Bayern Munich a few days before, so that didn’t help us.”